Making my way through the noise and traffic of Kathmandu, I arrive at the Tripureshwor Mahadev Temple where serenity awaits me. A security guard at the entrance asks me to make an entry in a register.” Where is the music museum?” I ask him and he points somewhere on the right.

As I walk into the premises of Music Museum of Nepal, I notice the huge black sarangi – a traditional stringed instrument – measuring more than 7ft tall and believed to be the largest sarangi in the world. Squeaky wooden staircase leads me to the first floor where photographs of sculptures depicting Hindu deities playing music instruments hang on the wall. The building has the smell old wooden buildings usually have and I can’t help but notice the run-down state the museum is in. I am unable to find someone to speak to and wonder if I am in the right place – that is, until I see Bijay.

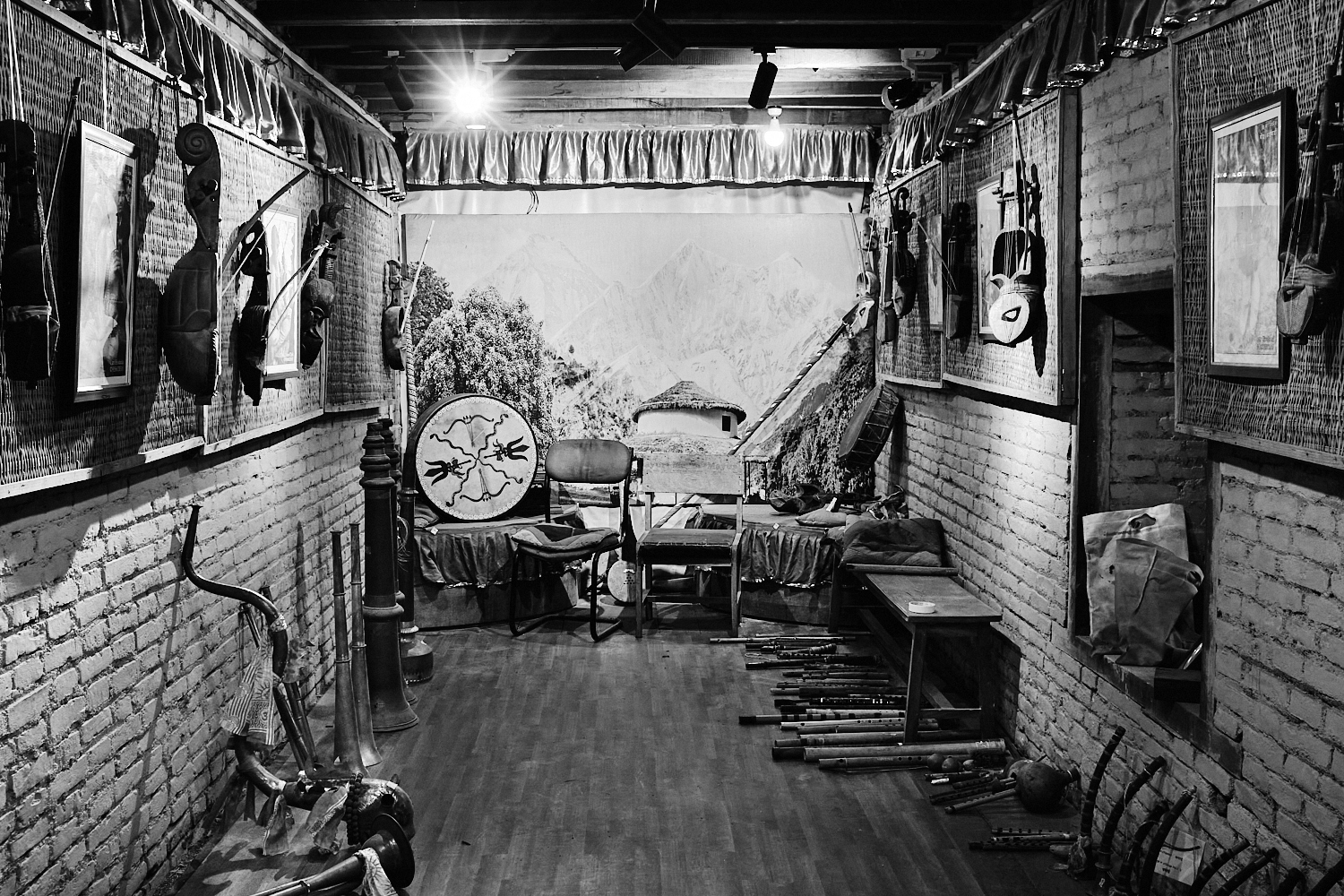

Bijay – who has worked at the museum for more than a decade – greets me and leads me to the section where any music and history lover would rejoice like pirates stumbling upon treasure. As he turns on the lights, I am speechless – struck by the beauty of these instruments, most of which are lying on the ground while the museum is engaged in the cumbersome job of labelling and cataloguing them. Images taken by photographer Jan Møller Hansen and researcher Dr. Carol Tingey hang on the walls around the museum. Tingey made several trips to Nepal between 1984 and 1992 when she recorded some 100 hours of folk and ritual music. The extensive collection is freely available from British Library.

I walk around to find some instruments I recognise – madal, dholak, dhimay, flute, sarangi, conch shell, and dhyangro to name a few. The first time I saw a dhyangro drum was in Gosaikunda during the shaman festival in 2021. Other instruments I recognise, they are usually seen in wedding ceremonies and some are played during festivals like Indra Jatra. Most other instruments – I had never seen them. Divided in nine groups – hundreds of these Nepali instruments are preserved thanks to the efforts of Mr. Ram Prasad Kadel, the founder and director of Music Museum of Nepal.

Kadel began researching, documenting, and collecting Nepali music instruments in 1995. The collection now consists of more than 1,000 pieces of 655 kinds of instruments collected from the highs of Himalayas to the plains of Tarai. Some of these instruments like panha mukha baja, jor murali (paired flute), haade bansuri, yaba mridanga, and rudra mridanga have gone extinct and are only found at the museum. 65 instruments were destroyed in the 2015 earthquake. Kadel has also authored two books listing Nepal’s musical instruments – Folk Musical Instruments of Nepal in 2004 and Musical Instruments of Nepal in 2007 in Nepali and English, respectively. The museum organises a yearly international folk music film festival which will be in its 13th edition this year.

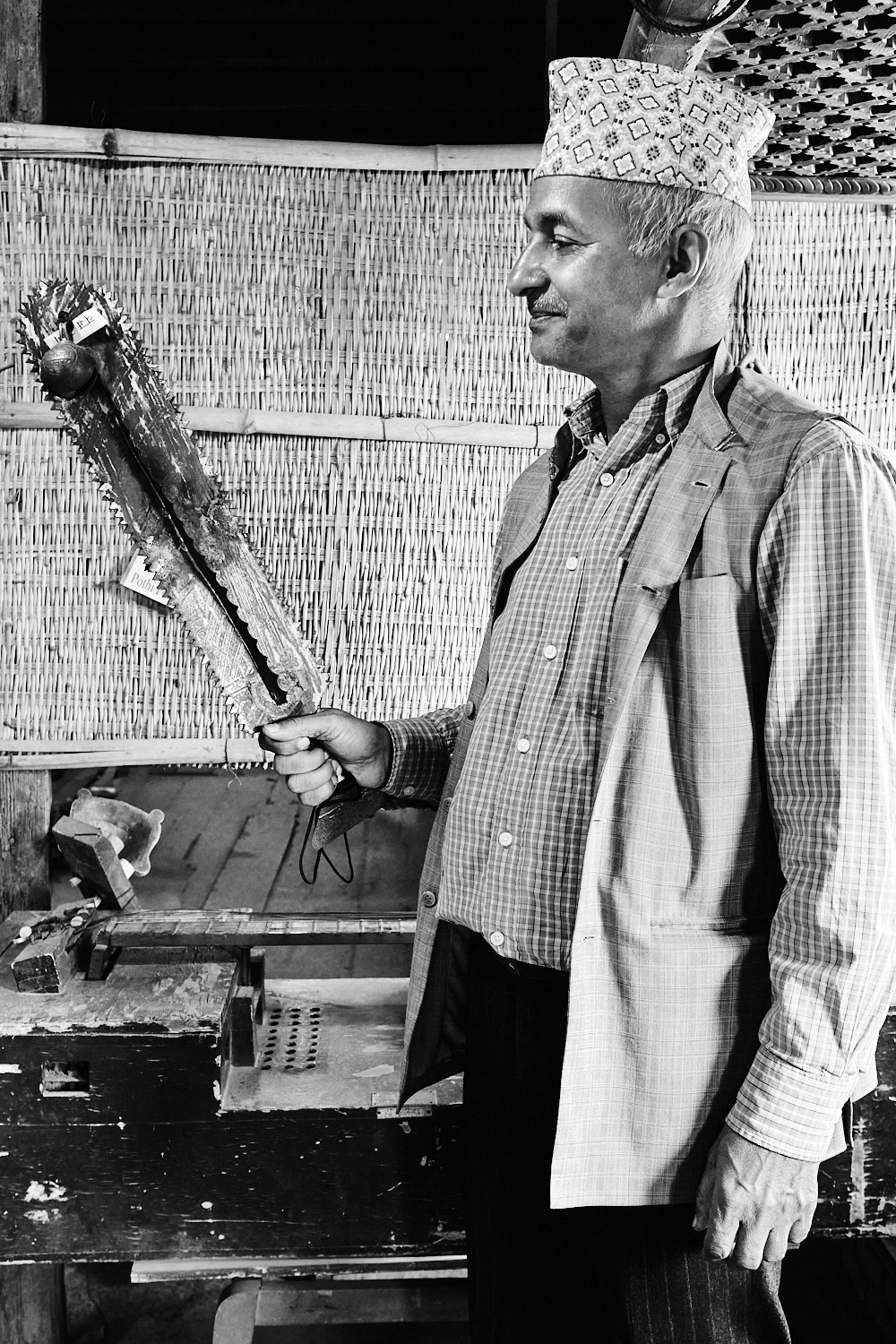

When I met Mr. Ram Prasad Kadel during my second visit to the museum, he had said within minutes that he is not a musician. So what led him to start the collection of these instruments and founding of the museum, I wonder.

“I started collecting the instruments and subsequently the museum as a guru dakshina (gifts/tribute offered to the master by the disciple) to my guru,” he says referring to his master Swami Akhandananda Saraswati from whom he learnt meditation. “My guru asked me to do something for the country and that’s what I am doing,” His eyes appear to be hazy as he mentions his guru and recounts his journey that spans nearly three decades.

I thank him for his efforts in preserving the cultural heritage of Nepal. These efforts are not only in collecting the instruments and running a museum, however. Kadel also has to constantly deal with threats of the museum being thrown out of its current home.

Kadel – who used to sell Thangka paintings to make a living – started the museum called Nepali Folk Musical Instrument Museum in 2002. It was housed temporarily in the premises of Bhadrakali temple in central Kathmandu. With the collection growing, the museum needed a larger space. After being allocated space by the Ministry of Culture, the museum moved in the premises of Tripureshwor Mahadev temple in 2007. It was also renamed as Music Museum of Nepal.

The temple, believed to be built in 1818 by queen Tripurasundari in memory of her deceased husband, King Rana Bahadur Shah, is under renovation after being destroyed in the 2015 earthquake.

Although housed in its current location for a long time, the museum is yet to find a forever home. The premises is leased to the museum by Guthi Sansthan, an independent institution tasked with preserving religious, cultural, and social heritage of Nepal. In 2016, the institution asked Kadel to vacate the premises as it had reached an agreement with Kathmandu University. The latter plans to construct a new building in the area where the museum stands and relocate its music department which is currently in Bhaktapur. The matter went to court and Kadel lost the case, making the future of the museum uncertain.

Within a week after my last visit to the Music Museum of Nepal, I came to know that the police had asked the museum premises to be emptied ‘within a day’ because the Guthi Sansthan had asked for police support for the same.

“It could be a matter of weeks before we pack all these invaluable pieces of history into a box and shut down,” Kadel had said in 2018. Not much has changed between then and now, it seems. Although the museum has managed to stay in its current house since the first notice of eviction, its future has remained shaky.

And the uncertainties aren’t only related to finding a new space. The lack of regular funding is further casting doubts over the museum’s future. Moreover, the museum does not see much visitors these days. While there used to be some 200 – 300 visitors everyday, footfall has reduced dramatically after the pandemic, according to Kadel.

The official website of Nepal Tourism Board makes no mention of Music Museum of Nepal.

As our conversation continues, I look out of a window to find young musicians practising some instruments in the soothing shade of the temple. I remain quiet for some time as I try to understand how does such an important institution come to a stage where it has to fight for its existence? What does it take for governments and private organisations to support valuable efforts of someone like Kadel? Would it be too naive to think that the museum, the university, and the government can work together to proudly save and exhibit the diverse cultural heritage? Or is it that ‘heritage’ only means buildings?

With uncertainties mounting over the relocation – or even the existence – of the museum, Kadel remains optimistic. What are his thoughts on the future of the museum, I ask him. “I don’t know politics, I am not rich or powerful, I don’t have powerful friends either. But it has worked until now and I am sure something will work out in the future, too. My guru’s blessings are with me,” says Kadel placing his right hand on his chest gesturing respect for his master.

I hope for Kadel’s words to remain true for generations to come.

Sources:

- Conversation with Mr. Ram Prasad Kadel, founder and director, Music Museum of Nepal

- Passing on folk instruments to the future, Mr. Ram Prasad Kadel, Founder, Music Museum of Nepal

- A disconcerting time for Nepal’s only music museum, The Kathmandu Post

- Country’s only folk musical instrument museum hits a sour note, The Kathmandu Post