When I was on my way to Nepal late-February this year, the pandemic wasn’t a ‘pandemic’ yet and terms like ‘lockdown’ or ‘social-distancing’ were still not widespread. As I travelled towards Nepal in packed buses and trains via Delhi, I had no idea that the world would soon come to a halt.

Early in March, I visited Kathmandu from where I went to Bhaktapur. Lost in the beautiful Durbar Squares of Bhaktapur and Kathmandu, I had not imagined that in less than three weeks, situation was going to be completely different. The chaotic beauty of Thamel was going to disappear and to be replaced by silence. Kathmandu’s air would catch a breath from heavy pollution. The mad traffic of the city would cease to exist.

After spending week in Kathmandu and Bhaktapur, I reached Pokhara, Nepal’s second largest city where I would spend eight months tucked away on a hill overlooking Phewa lake.

Pandemic, Nepal, and Myself

The first Covid-19 case in Nepal was detected as early as 23rd January when a student had returned from Wuhan. The second case was reported two months later.

On 12th March following the outbreak being declared a pandemic by WHO, the government of Nepal announced suspension of tourist visa and mountaineering expeditions. By 23rd March, the country was in complete lockdown. At this point, there were only two cases in Nepal on record.

In the following weeks, I occasionally went out to bring groceries. The lakeside area — Pokhara’s bustling tourist hub — was now empty. Farmers with their buffaloes, women carrying long grass for their cattle in big straw baskets on their back, people sitting outside their houses talking as children played nearby were the scenes you would occasionally come across.

Unable to run their businesses, many shops were up for sale. Failing to earn, staff who migrated from villages to find work in hotels, restaurants, tour companies and other businesses had no choice but to return home. Reports of increased suicide rate during the lockdown were heartbreaking and alarming.

Tourism is a top source of income for Nepal beside remittance and agriculture — supporting more than 1 million direct and indirect jobs. The landlocked country — home to the world’s eight out of ten highest mountain peaks — attracted 1.35 million tourists in 2018. This year was meant to be celebrated as ‘Visit Nepal 2020’ with a target to welcome two million tourists.

The pandemic put a break on everything.

In 2017, when I crossed the border to enter Nepal for the first time, I couldn’t tell much difference between India and Nepal. The transition from one country to the other is so smooth, it wouldn’t be possible for me to tell if I was in India or Nepal if it wasn’t for the ‘welcome’ signs on each side.

During all my subsequent visits, I always felt at ease, at home. India and Nepal share similarities in culture, festivals, cuisine, music, and overall lifestyle. Travelling in buses listening to Hindi music or watching Bollywood movies, I would nearly forget I am in a different country. I would always find people who speak Hindi, making me feel even more comfortable. Later on when I could speak Nepali — albeit not fluent — I was able to blend more with locals who welcomed me with an open heart. Feeling at ease in an unknown place gave me more confidence to approach people and talk to them, photograph them.

During the lockdown, I had a stretch of at least three months when I didn’t feel like picking up my camera and click a picture or write something. Many photographers were coming up with ideas like doing photoshoots on videocalls or while playing games. It took me a while before I managed to get over this and click something, anything.

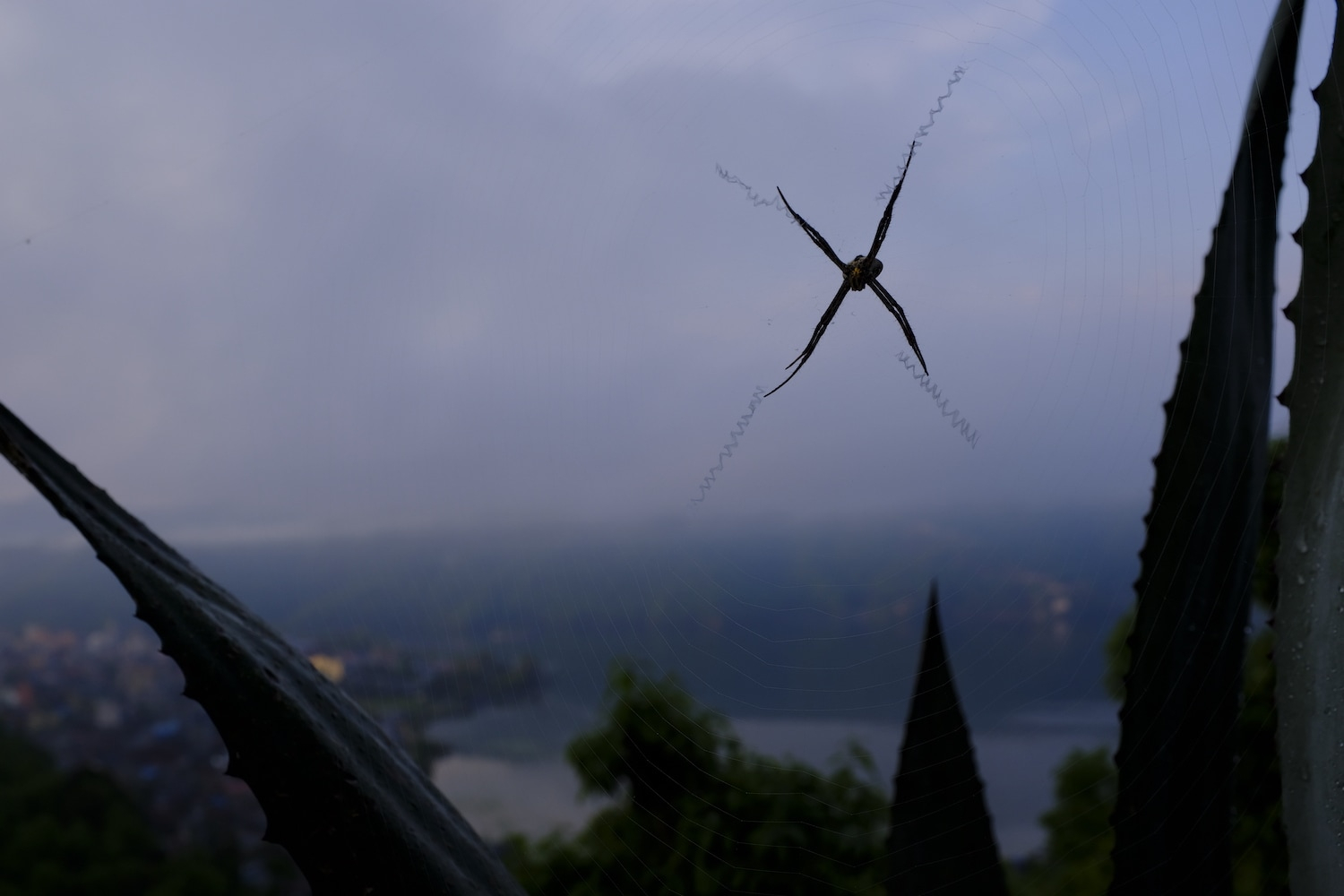

I started capturing pictures of flowers blooming around me. A spider that built a web on an agave plant outside my room and lived there through heavy rain — I started documenting it nearly everyday. One day I saw it trying to eat a big bug and the next day it was gone. Waking up to birds whisteling, observing ‘Woody the woodpicker’ as it bore a hole in a tree, feeding two very chatty babies, and disappearing some days later — in absence of contact with people, I came closer to the nature.

The lockdown also gave me an opportunity to learn cooking. Many recipes from my mother that I grew up eating, I tried to cook them on my own. To my surprise, I turned out to be good at it. While there was a time I used to think that I wasn’t patience enough, cooking during lockdown proved me wrong. Cooking can be meditative, I had heard. Now I agreed.

Nepal’s four-month long lockdown ended on 22 July with some restrictions in place. Local transport was allowed, followed by long-haul transport being allowed to run on full capacity. Flights, first decided to resume from 17th August, resumed from 1st September.

With Nepal’s biggest festivals Dashain and Tihar approaching, markets in Pokhara were bustling in early days of October. People were seen shopping for jewellery, clothes, footwear, and masks among other things. Restaurants and cafes remained mostly empty but food delivery was in demand. While being a part of the crowd, the pandemic didn’t seem to exist. Life in the street seemed usual — it felt good that life was returning to normal but that wasn’t completely true. With cases on the rise and economy on decline, ‘normalcy’ was far away from being reality.

From October 17th, Nepal was officially open for tourism and mountaineering. With flights still suspended in many countries and the pandemic far from over around the world, tourism industry wasn’t very optimistic about international visitors. As the long haul transport resumed and festivals neared, Nepalis began exploring their country — bringing some relief to businesses. Domestic tourism saw a considerable rise and airlines, hotels, tour operators etc. offered heavy discounts to the class of tourists they once ignored in favour of international visitors.

The 10-day Dashain festival began with ‘Ghatasthapana’ on 17th October. We were invited over for dinner by some neighbours. Celebrations and ceremonies largely remained limited within families as temples were not allowed to hold mass prayers. Some houses in the village sacrificed goats and invited friends and families. We were sent sel rotis that we enjoyed with fresh yoghurt from the village.

With the shopping and festive mood on the rise with Tihar festival — known as Diwali in India — getting closer, cases were expected to rise, too. Nepal’s already struggling healthcare was overwhelmed by the number of cases.

Although I had thought about leaving for India before, it wasn’t until this time I gave the thought more importance. There were no direct flights to India so travel time was to extend up to at least 24 hours. Eventually I decided to take a flight to Bhairawah and from there, cross the Sunauli border.

Five days before the beginning of Tihar celebration, I was en route to India. Things were different at the border this time — CRPF personnel checked your documents, asked you questions, and had a sniffer dog check your luggage. Before, you could just walk between the countries and no one would stop you.

After entering India, I reached Gorakhpur and stopped at my regular small biryani joint. Then I took a train to Lucknow and from there, a flight to Ahmedabad via Delhi. The next morning, I was back home where too, cases were to rise because of festive mood. I stayed in isolation for a week and monitored myself. On the eigth day, I was busy cooking something I had practiced in Nepal during the past few months.

Eight Months in Nepal During the Pandemic: Summary

When I left for Nepal late February, I had not imagined how worse the Covid-19 situation would turn out to be. Over the course of eight months, The weather changed from a halestorm to long monsoon to harsh sunny days, and mild winter. I had a snake visiting me at least three times in and near my room. A spider became my daily observation subject and a neighbour’s sneaky cat came to visit me nearly every evening. I came close to the nature around me. The urge to pick up the camera or to write something was lost for weeks.

The ongoing pandemic brought me closer to nature, kitchen, and myself. It taught me further to have patience and appreciate what I have. While I see no problem in not being able to ‘socialise,’ I wasn’t prepared to observe empty, lifeless streets. I learnt not to take life and its moments for granted. When I had the chance, I roamed around Pokhara clicking pictures of the life getting back on track.

Back in India, life seems to be going on as usual. I am not yet ready to be a part of it, but I will. Eventually.